Introduction

Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens has become a global phenomenon, selling over 45 million copies and translated into 65+ languages. With its sweeping take on human history—from foragers to tech founders—it’s praised for being bold, clear, and wildly readable.

But that’s where the problem begins.

While Sapiens is celebrated for simplifying the story of humanity, many experts argue it simplifies too much. Anthropologists, archaeologists, and scientists have all pointed out serious flaws—accusing Harari of prioritizing storytelling over solid evidence.

This post isn’t here to tear the book down. It’s here to read it more critically. We’ll break down three common myths Sapiens leaves behind—and why it’s crucial to question even the most convincing narratives.

Myth #1: The “Cognitive Revolution” Was a Sudden Breakthrough

In Sapiens, Harari presents the “Cognitive Revolution” as a sharp turning point in human history. Around 70,000 years ago, he claims, Homo sapiens suddenly gained the ability to imagine, communicate abstractly, and cooperate in large groups—giving us a decisive edge over other human species.

It’s a bold claim. But many researchers argue it oversimplifies what was actually a much slower, messier process.

Cognitive Development Was Gradual

Anthropological and archaeological evidence shows that cognitive evolution unfolded gradually, not in a single moment. Traits like symbolic behavior, advanced tool use, and social complexity didn’t appear overnight—and they weren’t unique to Homo sapiens. Neanderthals and other hominins demonstrated similar abilities long before the supposed “revolution.”

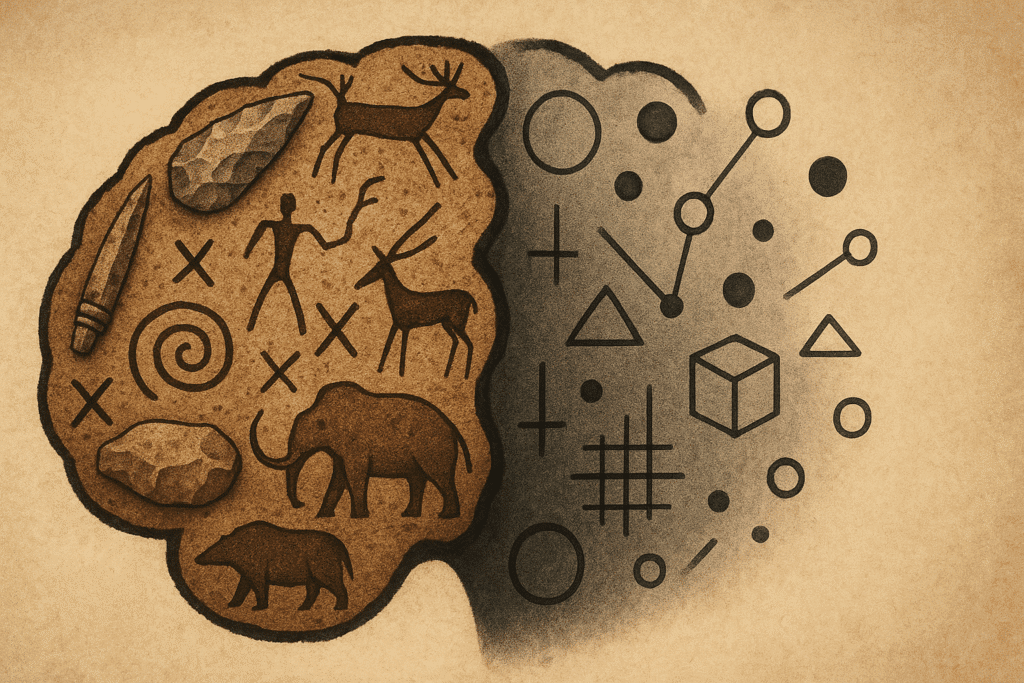

The “Revolution” Framing Is Misleading

The term “Cognitive Revolution” suggests a sudden, transformative shift. But according to scholars like Sandy Hobbs and Jeremy Burman, that framing distorts how evolution actually works. Changes in cognition happened in stages, over long periods, and across multiple hominin species. The word “revolution” imposes a dramatic break where none existed.

More Narrative Device Than Scientific Consensus

Critics argue that Harari’s framing is less about science and more about storytelling. It packages human evolution into a neat, digestible plot—something that’s easier to follow but far less accurate. As The Psychologist (British Psychological Society) notes, calling it a single revolution ignores the mosaic nature of evolution and the shared cognitive traits across species.

In short, Harari’s “Cognitive Revolution” may be a great story—but it’s not a settled scientific fact.

Myth #2: The Agricultural Revolution Was “History’s Biggest Fraud”

In Chapter 5 of Sapiens, Harari drops one of his most provocative claims: that the Agricultural Revolution was “history’s biggest fraud.” Instead of celebrating it as a major step forward, he argues that farming made human life worse. According to this view, early agricultural societies worked longer hours, ate a narrower and less nutritious diet, and became more vulnerable to disease and social inequality than their hunter-gatherer ancestors.

It’s a bold reframing of one of history’s most significant turning points. But as with many of Harari’s claims, the argument relies on sweeping generalizations—and leaves out important nuance.

Agriculture Wasn’t a Simple Fall From Grace

Harari tends to portray pre-agricultural societies as peaceful, egalitarian, and well-fed, while casting early farmers as overworked and miserable. This creates a tidy contrast, but the historical reality is far more complex. The shift from foraging to farming didn’t happen overnight, and it didn’t follow the same pattern everywhere.

In fact, many communities transitioned slowly, maintaining hybrid economies that combined cultivation, herding, and seasonal foraging. In some regions, agriculture actually improved diet and stability. In others, foraging remained more practical for centuries. Context mattered—climate, geography, available resources, and social organization all influenced whether agriculture was a benefit or a burden.

To frame the entire Agricultural Revolution as a “fraud” ignores this regional and temporal diversity. It reduces a multifaceted, centuries-long transition to a single, pessimistic headline.

Long-Term Gains Often Get Overlooked

It’s true that early farmers faced serious challenges. The first generations may have worked harder and suffered more disease due to sedentary life, close proximity to animals, and reliance on fewer food sources. But focusing only on these short-term struggles misses the long-term picture.

Farming laid the foundation for some of humanity’s most transformative developments. Agriculture enabled population growth and permanent settlements, which in turn supported the rise of cities, governments, organized religion, trade, and technological innovation. Writing systems, large-scale cooperation, legal codes, and the scientific method all emerged from post-agricultural societies. These advances simply wouldn’t have been possible in small, nomadic bands.

Harari briefly acknowledges some of these developments, but his core narrative emphasizes loss over progress. He underplays the fact that agriculture created conditions for civilization itself.

A Philosophical Claim Framed as Scientific

One of Harari’s most attention-grabbing lines is that wheat domesticated us—not the other way around. He suggests that humans became enslaved to their crops, working harder to serve the needs of a plant rather than their own well-being. It’s a clever metaphor, but it leans more on philosophy than science.

From an evolutionary standpoint, agriculture was a success story. It enabled Homo sapiens to expand, reproduce, and dominate ecosystems across the globe. Whether individuals were “happier” is beside the point—natural selection favors what works for survival and reproduction, not personal fulfillment. Agriculture didn’t betray human nature; it accelerated our species’ evolutionary trajectory.

Critics have noted that Harari’s framing imposes a modern lens—concerned with happiness and work-life balance—onto prehistoric developments. It’s a compelling story, but it risks projecting present-day values onto the past.

The Reality: A Trade-Off, Not a Fraud

The Agricultural Revolution wasn’t a one-sided disaster, nor was it an instant utopia. It was a massive, uneven, and deeply consequential shift in how humans lived. It brought both benefits and burdens, with impacts that varied across regions and centuries.

Some people gained more than others. Inequality grew. New challenges emerged. But to call it a fraud is to ignore the full scope of what agriculture made possible—not just for individuals, but for the human species as a whole.

In the end, Harari’s framing might be provocative, but it oversimplifies a transformation that shaped the modern world.

Myth #3: Human Cooperation Depends Entirely on “Shared Fictions”

One of the most quoted ideas from Sapiens is Harari’s theory that human societies are built on “shared fictions.” Religion, money, governments, and corporations—he argues—are imagined realities. They exist only because we collectively agree they do. This, he says, is what sets Homo sapiens apart: the ability to unite millions of strangers around abstract concepts.

According to Harari, without these fictions, large-scale cooperation would collapse. Humans would revert to small, kin-based groups, unable to coordinate beyond their immediate tribe.

It’s a compelling idea—and one that clearly resonates with modern readers. But many scholars argue that it oversimplifies the roots of human cooperation and misunderstands how real-world systems work.

Human Cooperation Isn’t Just About Imagination

Harari builds his case around the idea that belief in shared stories drives cooperation. But critics point out that this reduces a deeply complex behavior to a single mechanism. Cooperation isn’t just a product of collective imagination—it’s also hardwired into us through biology and shaped by culture.

Humans evolved with strong instincts for empathy, reciprocity, and fairness. We’re social animals with a deep sensitivity to group norms and reputation. These traits existed long before modern religions or financial systems—and they continue to shape behavior today, often independently of belief in abstract constructs.

In short, our ability to work together isn’t just a storytelling trick. It’s also the result of evolutionary psychology, emotional intelligence, and real-world incentives.

Not All Constructs Are “Fictions” in the Same Way

Harari’s framework puts things like religion, money, and the legal system in the same category: fictions that exist only in our minds. But this framing risks blurring important distinctions.

Yes, money has no inherent value—it works because we agree it does. But that’s not quite the same as myth or religion. Economic systems, legal frameworks, and political institutions are grounded in enforceable rules, measurable outcomes, and real-world consequences. They’re not arbitrary beliefs—they’re structured systems designed to solve real problems.

When Harari calls them fictions, it can imply they’re fragile or imaginary. But many social constructs are resilient precisely because they’re functional. They emerge, adapt, and persist not just because people “believe” in them, but because they serve a tangible purpose.

Institutions, Trust, and Enforcement Matter

Another key piece missing from Harari’s narrative is the role of institutions. Cooperation at scale doesn’t rely solely on belief—it also depends on trust, enforcement, accountability, and system design.

Take traffic laws. People don’t obey them because they believe in a myth about stop signs. They follow them because the rules are clear, enforcement is predictable, and the benefits—safety, order, efficiency—are real and shared. The same is true of contracts, taxes, and public health systems.

Large-scale cooperation often relies on engineered systems that work regardless of what people “believe.” Harari’s theory overlooks how much of human coordination is built on structure, not just imagination.

A Philosophical Idea, Not a Scientific Model

Harari’s argument about shared fictions is clever, and there’s truth in it. Humans do rely on stories to give meaning to life and legitimacy to institutions. But to claim that all cooperation depends on fiction is to ignore biology, sociology, and political science.

As scholar Darcy Moore puts it:

“Harari’s idea that all large-scale cooperation depends on shared fictions is clever, but it’s also philosophically shallow. It ignores the role of real incentives, evolved psychology, and institutional frameworks.”

It’s a great hook—but not a full explanation.

Conclusion: Sapiens Is Worth Reading—But Not at Face Value

Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens is a rare phenomenon: a history book that became a global bestseller, sparked philosophical debates, and reshaped how millions of readers think about humanity. Its sweeping narrative, provocative claims, and elegant prose make it a compelling read. But compelling doesn’t always mean correct.

As we’ve seen, Sapiens often trades nuance for narrative, evidence for elegance, and complexity for clarity. Harari’s framing of the Cognitive Revolution, the Agricultural Revolution, and the role of “shared fictions” simplifies deeply contested academic debates into digestible soundbites. That’s not inherently bad—but it’s not the same as rigorous scholarship.

Final Takeaway

Sapiens is best approached not as a textbook, but as a conversation starter—a gateway into anthropology, history, and philosophy. It raises important questions, but it doesn’t always offer reliable answers. If you read it with curiosity and a critical eye, it can be a powerful tool for learning. If you take it at face value, it risks reinforcing myths rather than dismantling them.

“Harari is a brilliant storyteller, but not always a careful historian. His book is fascinating—but flawed.”

— Bethinking.org Critical Review

Alternative Books to Sapiens

If you found Sapiens thought-provoking but want something more grounded in scholarship—or just a different lens on human evolution, culture, and society—here are some excellent alternatives recommended by historians, scientists, and critical readers:

1. Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond

- Focus: Environmental and geographic factors shaping civilizations

- Why Read It: Offers a data-driven explanation for why some societies advanced faster than others—without relying on speculative storytelling

- Critique of Sapiens: More rigorous in its treatment of causality and historical development

🔗 Read more

2. The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee

- Focus: The history and science of genetics

- Why Read It: Combines personal narrative with deep scientific insight into heredity, identity, and evolution

- Critique of Sapiens: Provides the biological depth that Sapiens often glosses over

🔗 Explore the book

3. The Sixth Extinction by Elizabeth Kolbert

- Focus: Human-driven mass extinction and environmental impact

- Why Read It: A Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation into how Homo sapiens are reshaping the planet

- Critique of Sapiens: Grounded in fieldwork and scientific reporting rather than philosophical speculation

🔗 See the book

4. The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan

- Focus: A global re-centering of history through Eastern trade routes

- Why Read It: Challenges Eurocentric narratives and offers a broader view of cultural exchange

- Critique of Sapiens: More historically balanced and less deterministic

🔗 Discover more

5. The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins

- Focus: Evolutionary biology and gene-centered natural selection

- Why Read It: A foundational text in understanding how evolution shapes behavior

- Critique of Sapiens: Offers scientific rigor where Harari leans into metaphor

🔗 Learn more

Would you like a comparison chart of these books vs. Sapiens, or a reading roadmap based on your interests (e.g., evolution, culture, politics)? I’d love to help you build that next!

FAQs

Is Sapiens a scientific work?

No. It’s popular science, not peer-reviewed research. Harari is a historian, and the book simplifies complex topics for general readers.

Did the “Cognitive Revolution” really happen 70,000 years ago?

Not exactly. Most experts believe cognitive abilities evolved gradually, and other hominins like Neanderthals also showed signs of complex thinking.

Was the Agricultural Revolution really “history’s biggest fraud”?

That’s an overstatement. Early farming had downsides, but it also enabled cities, technology, and long-term progress. Harari’s take is more philosophical than scientific.

Are “shared fictions” the only reason humans cooperate?

No. Shared beliefs help, but cooperation also relies on language, empathy, trust, and social instincts—things Harari downplays.

Should I still read Sapiens?

Yes—but read it critically. It’s a great starting point, not a definitive source.